Ultımate Basic Abdominal Ultrasonography Training Guide

Table of Contents

Abdominal ultrasonography is one of the fundamental imaging modalities frequently used in emergency medicine, internal medicine, gastroenterology, and surgical disciplines. This method facilitates clinical decision-making thanks to its non-invasive, portable, and rapid nature.

This training guide covers the ultrasonographic anatomy, imaging techniques, and both normal and pathological findings of key organs such as the liver, gallbladder, pancreas, spleen, kidneys, and bladder. It is designed in an easy-to-understand format based on the information presented in the lecture and is aimed at students.

Liver

The liver is located in the right upper abdominal quadrant, just beneath the diaphragm. Anatomically, it is bordered superiorly by the diaphragm, inferiorly by the right kidney and gallbladder, and on the left by the stomach and spleen. It measures approximately 25–30 cm in width, 14–16 cm in height, and 8–10 cm in anteroposterior length.

For ultrasonographic examination, the best approach is usually through the subcostal or intercostal spaces. Having the patient in a right lateral decubitus position provides better visualization of the liver. Evaluation can be performed in transverse, sagittal, and oblique planes.

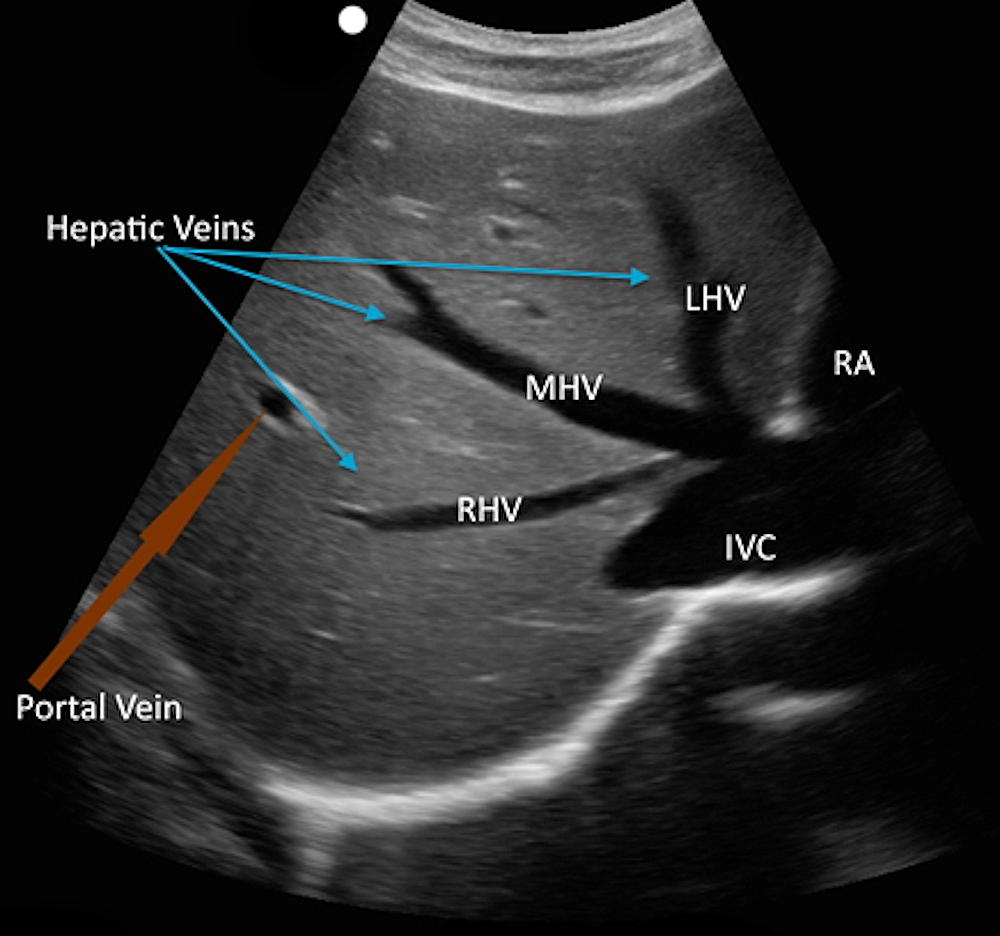

The convergence of the hepatic veins creates the characteristic “white star” appearance, marking the confluence with the inferior vena cava in the midline (Figure 1).

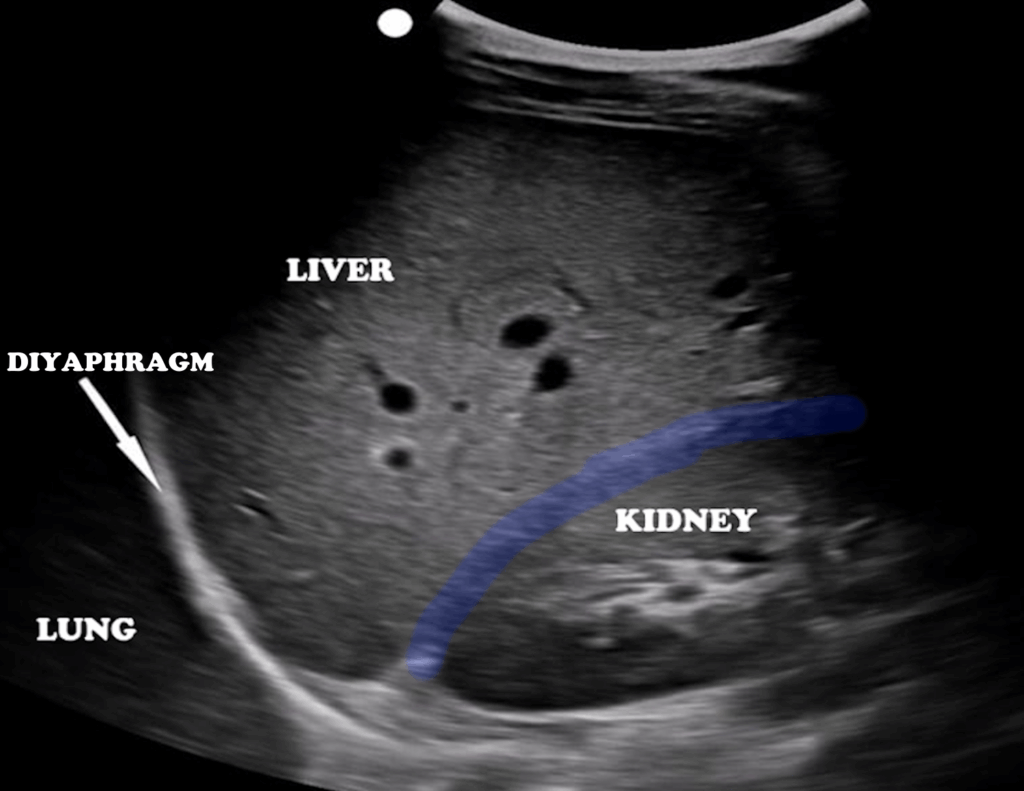

The hepatic parenchyma appears homogeneous and moderately echogenic (Figure 2).

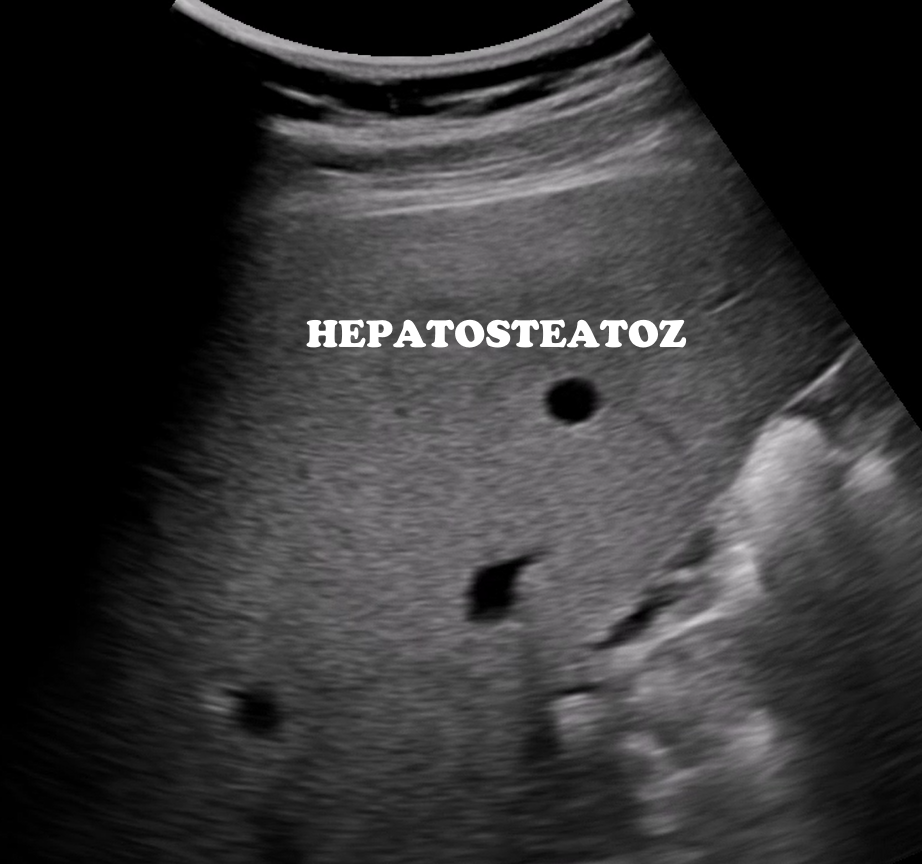

Mass lesions typically appear as heterogeneous or hypoechoic areas (Figure 3), while hepatic steatosis causes increased echogenicity of the parenchyma (Figure 4).

Abscesses appear as heterogeneous structures with hyperechoic components within a hypoechoic background (Figure 5), whereas cystic lesions are anechoic, well-defined, and characterized by posterior acoustic enhancement (Figure 6).

Gallbladder

The gallbladder is located on the inferior surface of the liver, along the right midclavicular line. The probe is usually placed just below the costal margin along this line, with the indicator directed toward the patient’s head. Compared to the hepatic parenchyma, the gallbladder has more hyperechoic walls, and its contents appear anechoic (fluid-filled).

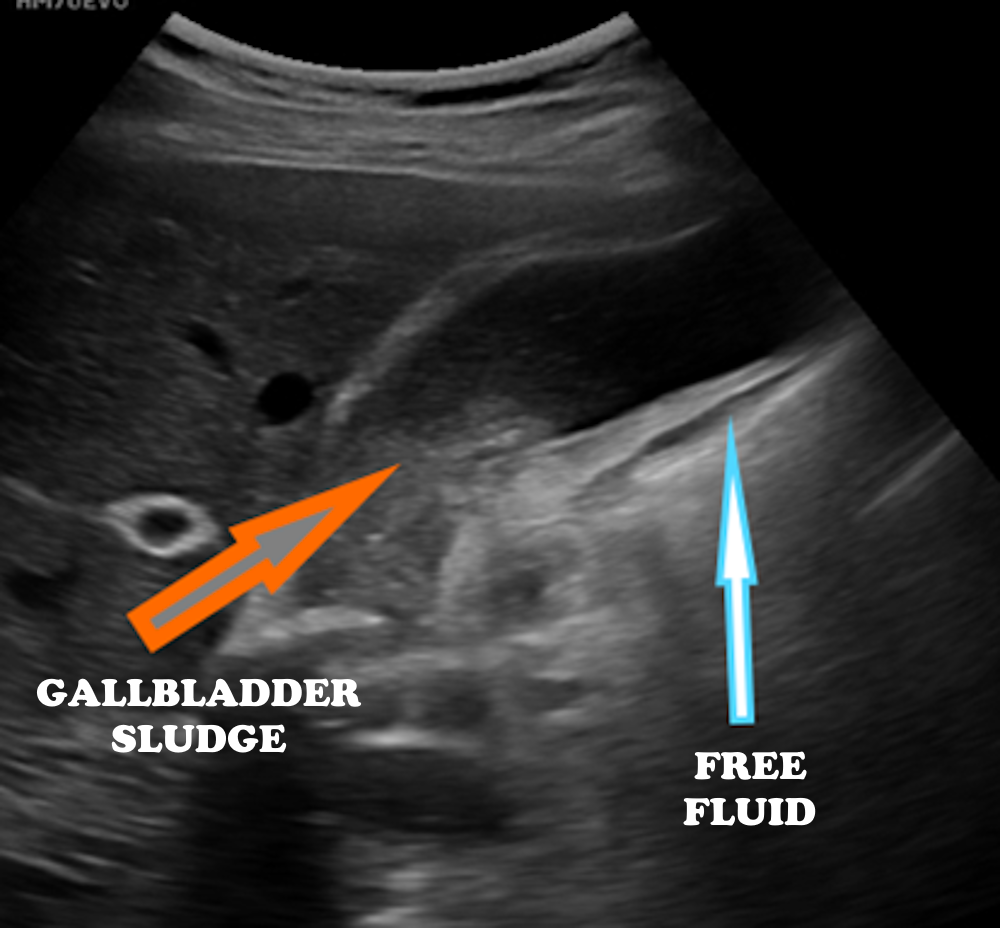

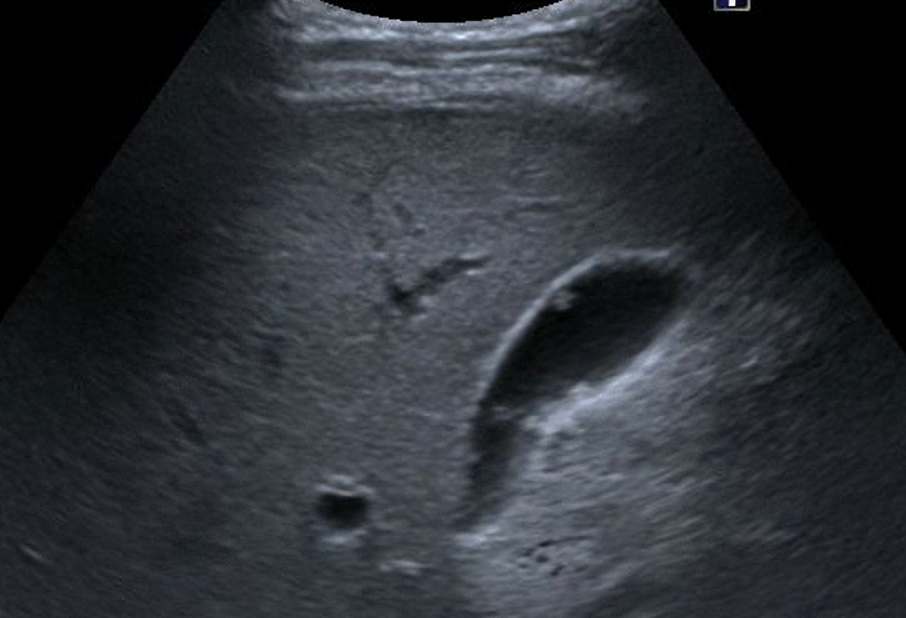

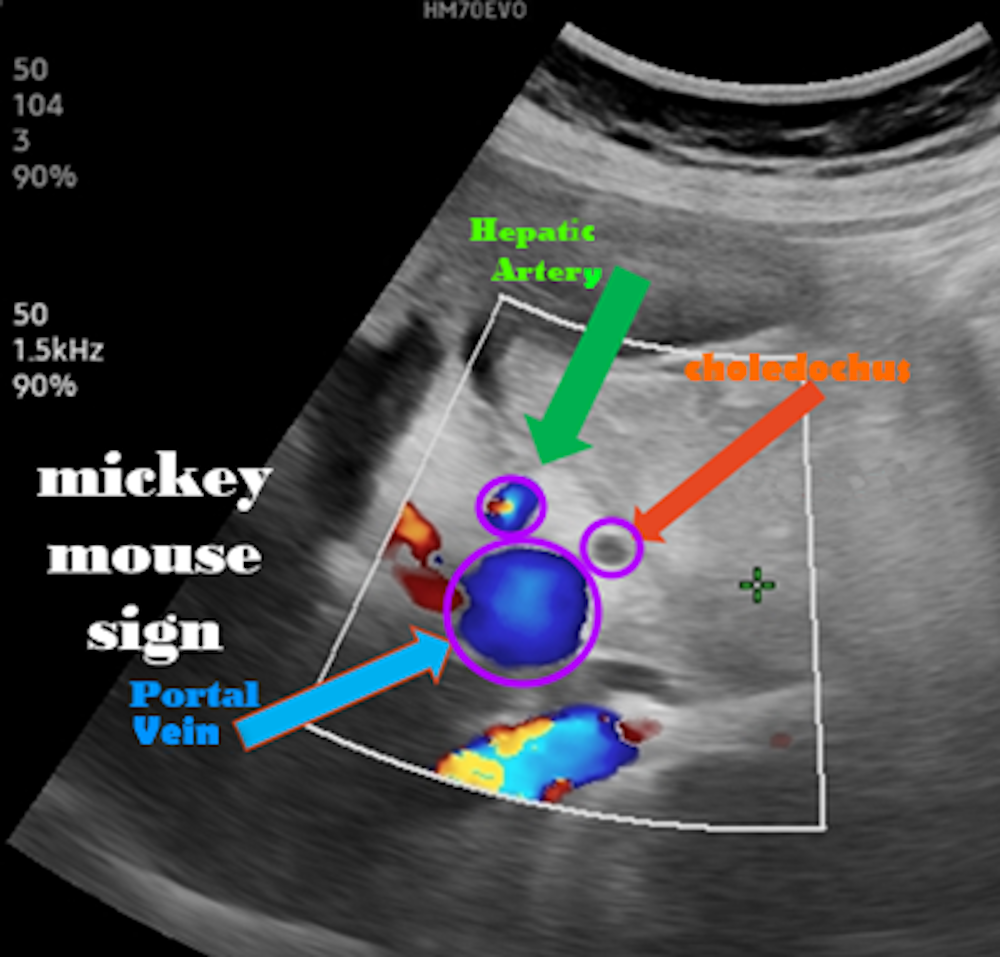

A normal gallbladder measures approximately 10 cm in length and 2–4 cm in diameter, with a wall thickness of less than 3 mm. Gallstones typically appear as hyperechoic foci that produce posterior acoustic shadowing (Figure 7). In acute cholecystitis, increased wall thickness, pericholecystic fluid, and a positive sonographic Murphy’s sign may be observed (Figures 7 and 8). In cases with biliary sludge, a homogeneous fine internal echogenicity is noted (Figure 8). Polyps appear attached to the gallbladder wall and do not move with changes in patient position (Figure 9). Visualization of the main portal triad during gallbladder ultrasonography is crucial for identifying hepatobiliary system pathologies (Figure 10).

Pancreas

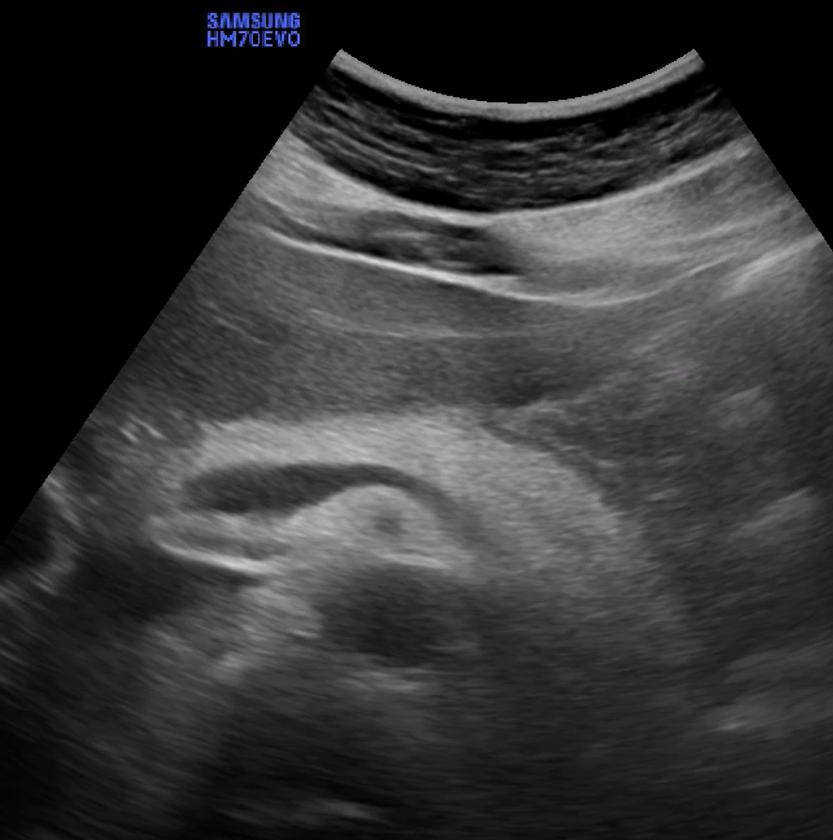

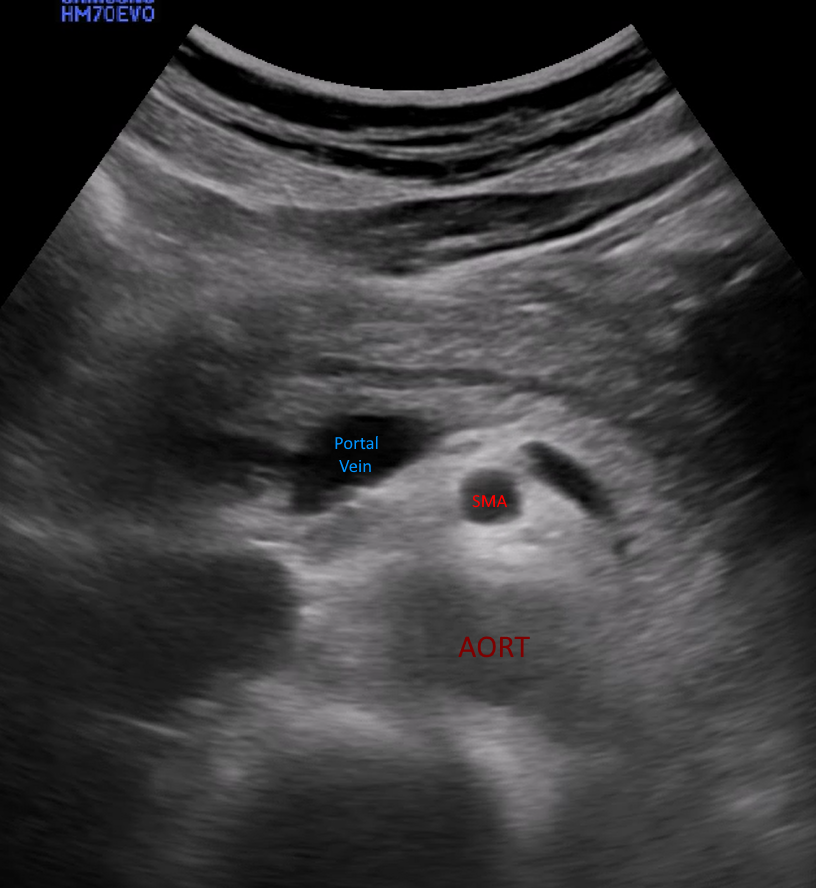

The pancreas is located in the midline of the abdomen and is often difficult to visualize. It is evaluated in the transverse plane using a curvilinear probe placed in the subxiphoid area, with the probe marker directed toward the patient’s right side.

The head of the pancreas lies adjacent to the duodenum, while the tail extends toward the spleen. The pancreatic parenchyma typically appears isoechoic or hyperechoic, with echogenicity increasing with age (Figure 11). In the transverse view, the pancreas can be identified between the left lobe of the liver and the splenic vein. In acute pancreatitis, the pancreas appears enlarged and heterogeneous, often accompanied by peripancreatic fluid collections. In chronic pancreatitis, calcifications and ductal dilatation are characteristic findings (Figure 12).

Spleen

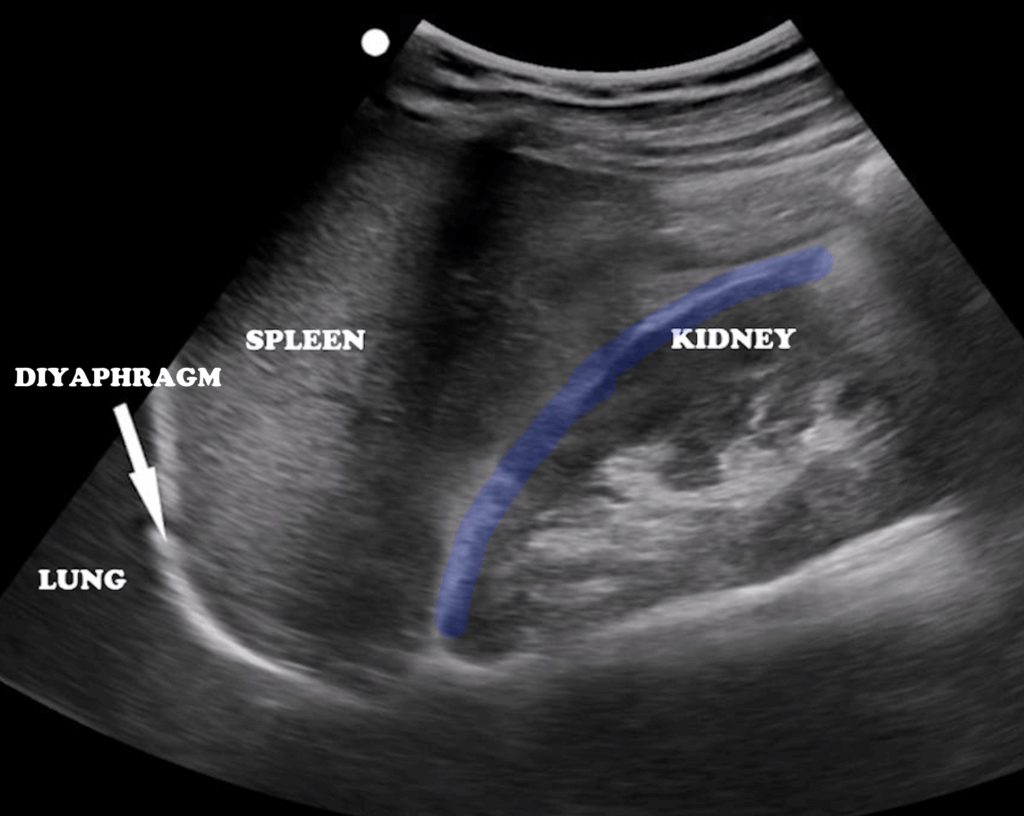

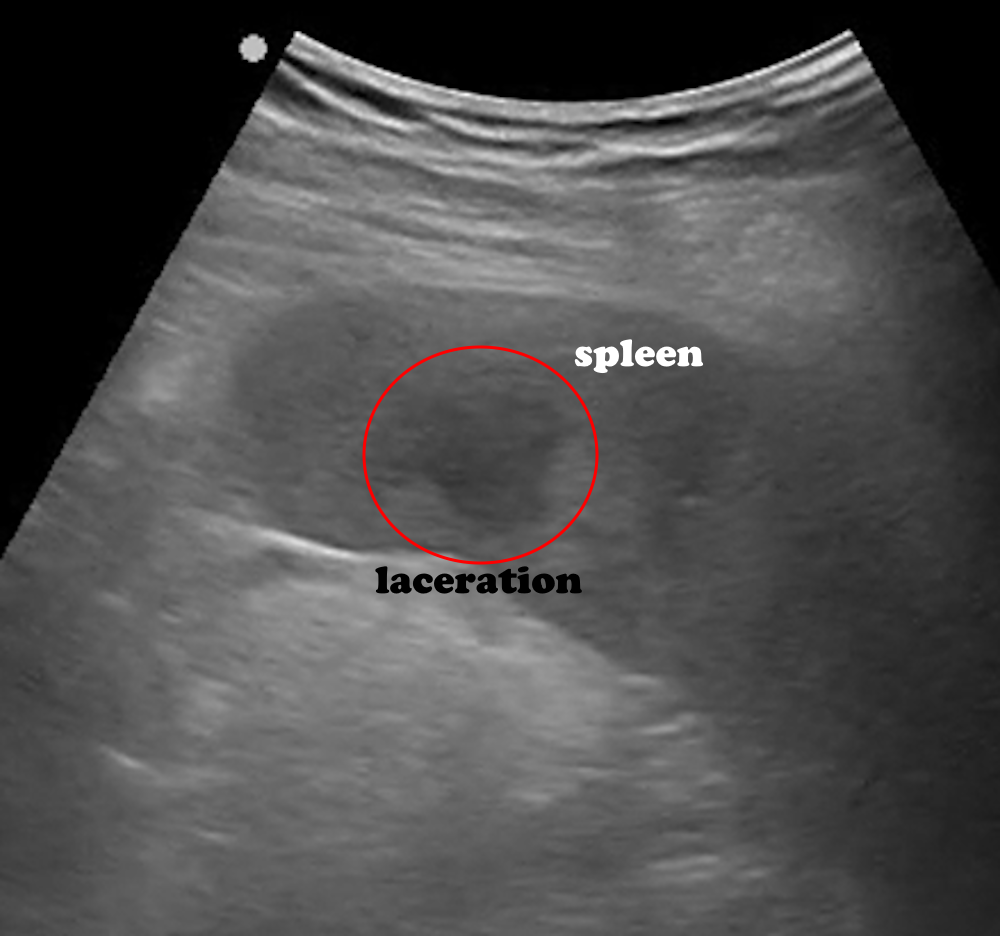

The spleen is located in the left upper abdominal quadrant, just beneath the diaphragm. Its anatomical relations are as follows: superiorly the diaphragm, anteriorly the fundus of the stomach, posteriorly the left kidney, and medially the tail of the pancreas (Figure 13). Compared to the liver, the spleen appears more hyperechoic and homogeneous. Its average dimensions are 10 cm in length, 7–8 cm in width, and 4.5 cm in thickness. For imaging, the patient lies in a supine position, and the probe is placed along the posterior axillary line through the left lower intercostal spaces. Disruption of the homogeneous echotexture is significant for identifying lacerations due to trauma (Figure 14), infarction, or the presence of perisplenic fluid.

Kidneys

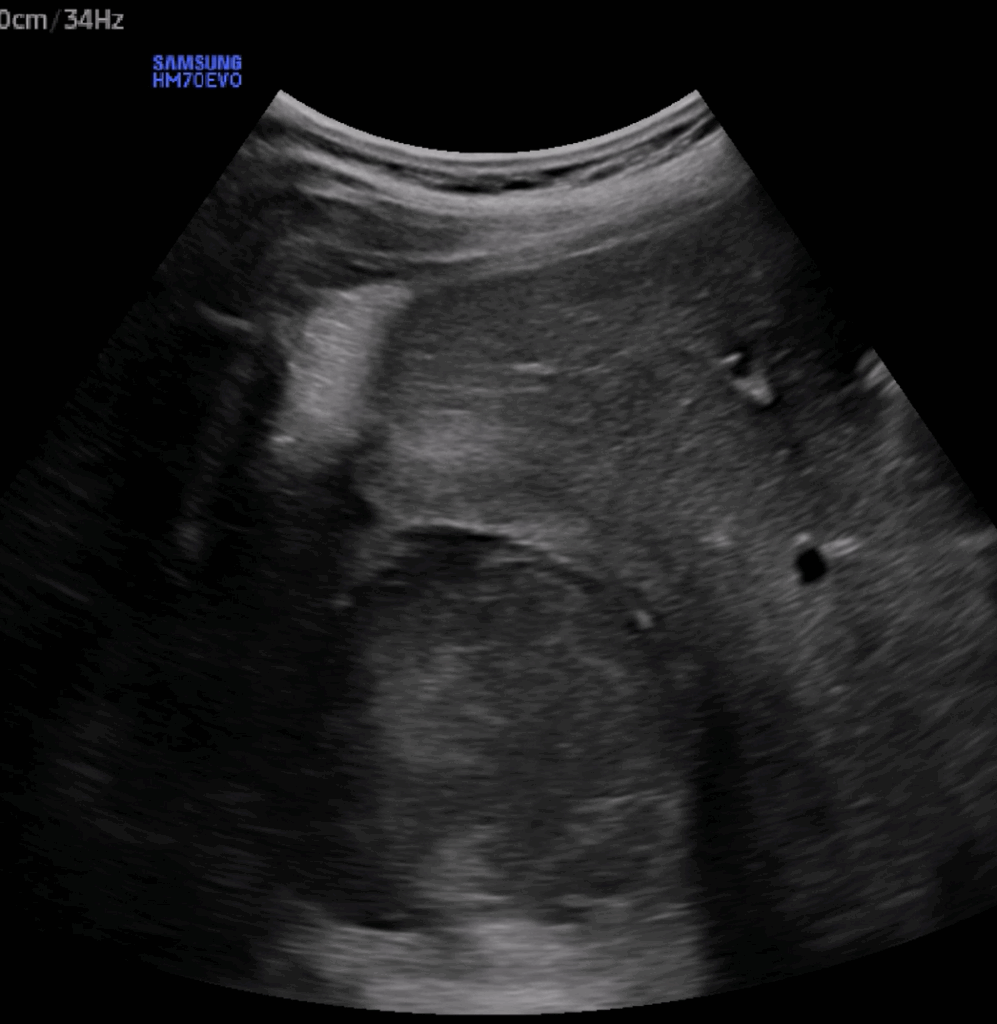

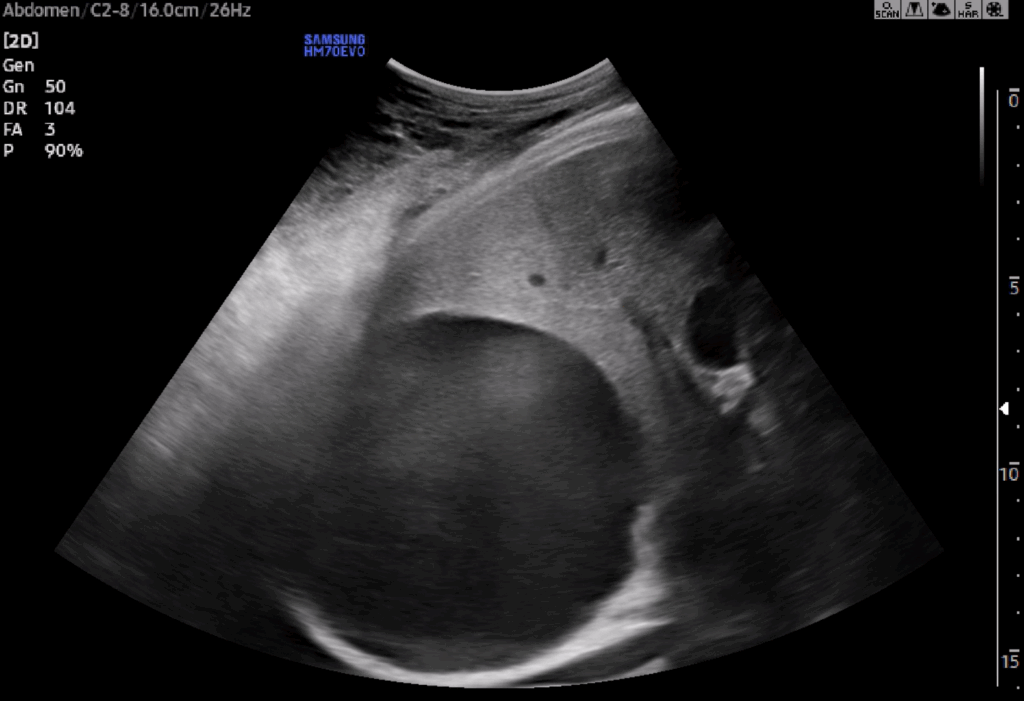

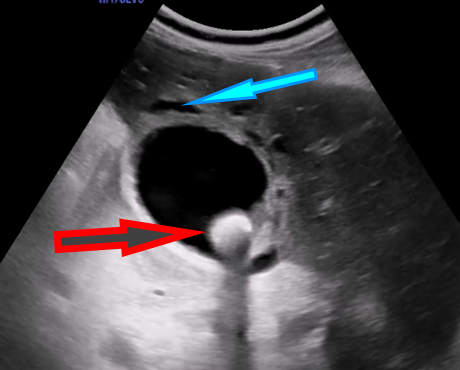

The kidneys are retroperitoneal organs. The right kidney is located just below the liver and is therefore easier to visualize, whereas the left kidney lies slightly higher, making it more challenging to image. For optimal assessment, intercostal and subcostal approaches should be combined.The renal cortex typically appears hypoechoic, while the renal sinus is hyperechoic (Figure 15). Hydronephrosis is evaluated based on the degree of dilatation of the collecting system. In Grade 1, there is a mild blunting of the calyceal fornices (Figure 15), while in Grade 4, marked ballooning and cortical thinning are observed (Figure 16). In nephrolithiasis, stones appear as hyperechoic foci with posterior acoustic shadowing (Figure 17).

Bladder and Pelvic Structures

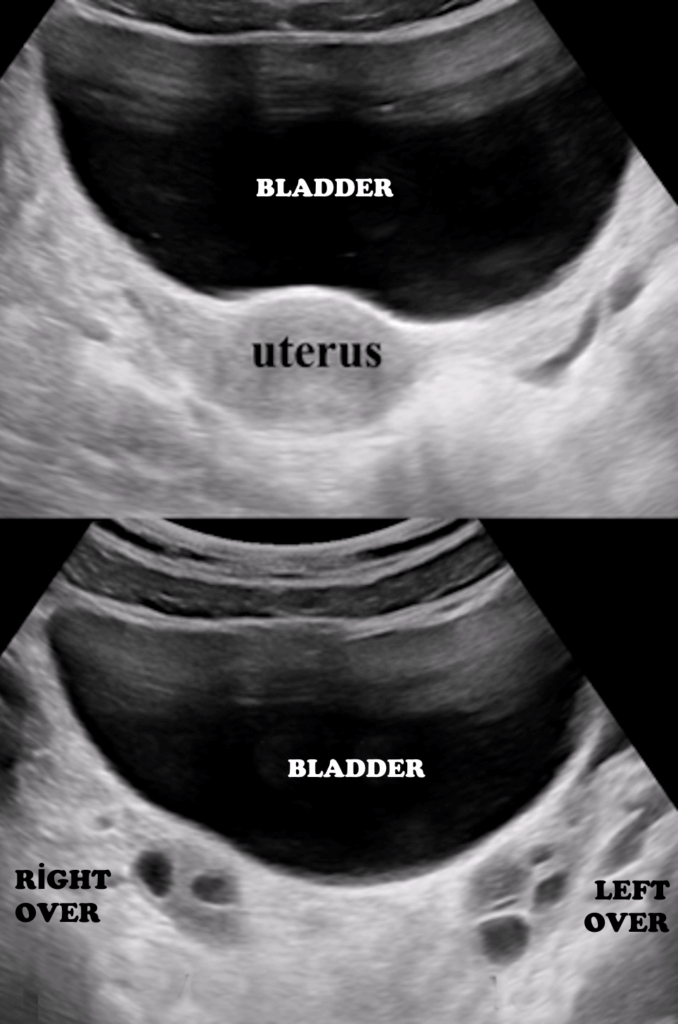

The bladder is located in the pelvis, posterior to the symphysis pubis, and is evaluated using a transabdominal approach. The best images are obtained when the bladder is moderately filled. The probe is placed on the lower abdominal wall, in contact with the pubic bone. Imaging should be performed in both transverse and sagittal planes.

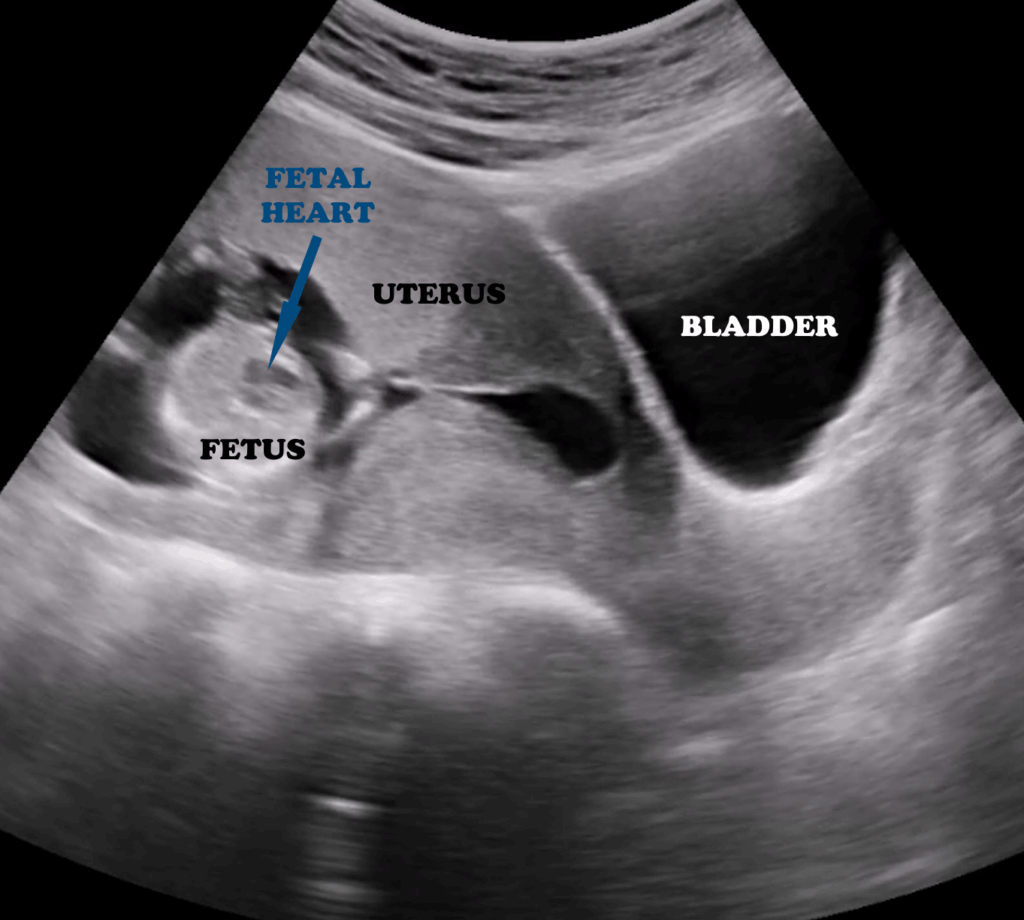

The bladder lumen appears anechoic, while the walls are smooth and hypoechoic (Figure 18).In female patients, pelvic ultrasound also includes the evaluation of the uterus and ovaries (Figure 18). The uterus is recognized by its characteristic “double line” appearance, and in pregnancy, the embryo may be visualized (Figure 19).

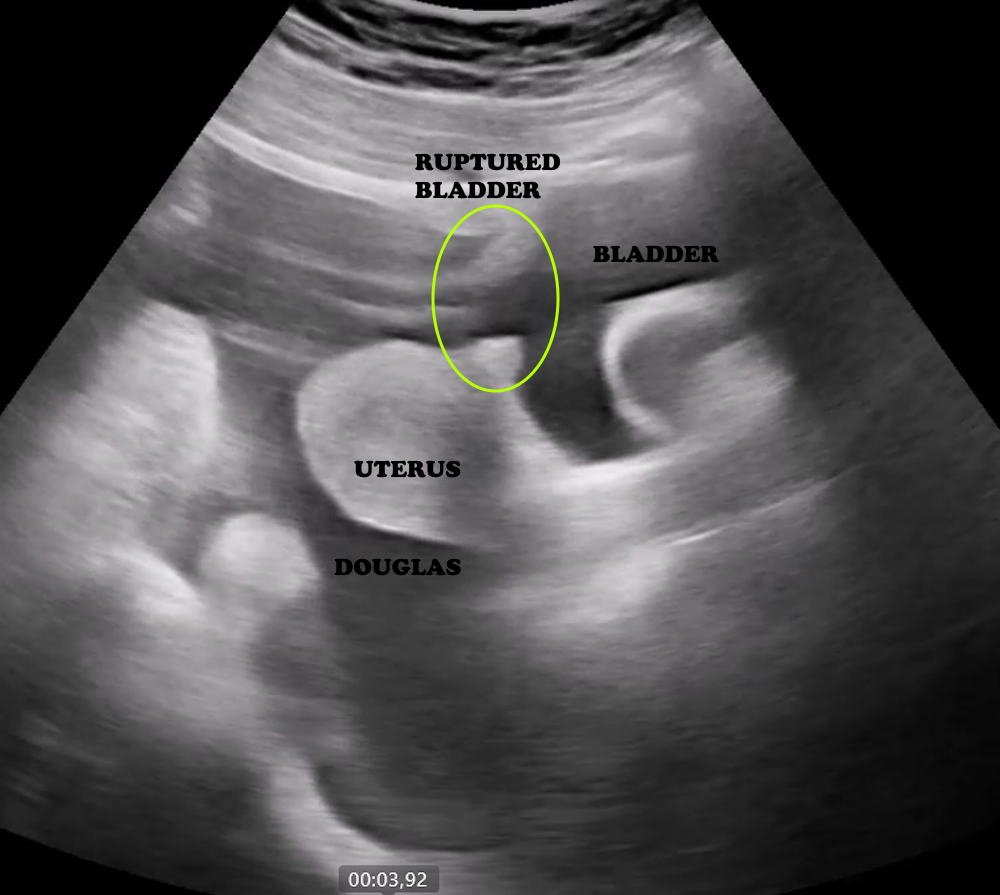

Bladder rupture is identified by irregularity of the wall and the presence of extraluminal fluid accumulation (Figure 20).

Hazırlayan: Dr. Ramazan Ünal

Tarih: 2025